If you follow me on Instagram or subscribe to my newsletter, you may have heard me gush over

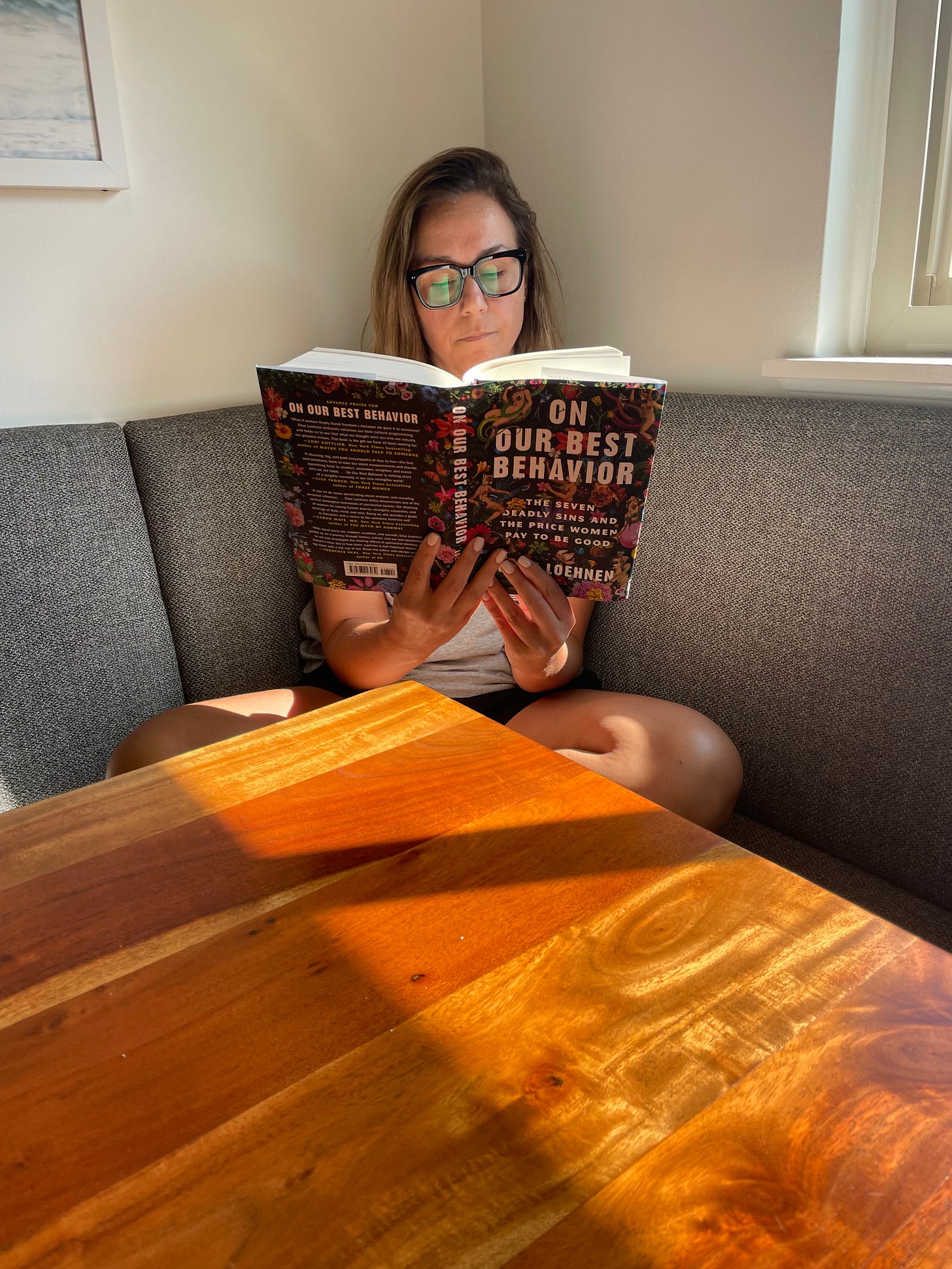

, author and host of the podcast, . She’s ghostwritten 11 books, five of which are New York Times bestsellers. In May, her first book under her name arrived, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good. I preordered it, read it, and loved it. I have recommended it to anyone who has talked to me for longer than five seconds.

In On Our Best Behavior, Elise examines the seven deadly sins and how they are weaved into our culture and seeded into women, tethering us, unconsciously, to beliefs about what it means to be “good.”

Loehnen explores “sloth,” one of the deadly sins, and describes how women use their productivity, or their level of busyness, to measure their worth or value. She writes, “Believing sloth to be sinful, we deny ourselves rest.”

I see this with women and especially mothers. We subscribe to the idea that a good mom maintains an orderly home and raises cooperative, polite, well-mannered children. Anything that falls short of this ideal results in feelings of inadequacy.

If you’re anything like me, being perceived as lazy or unproductive is terrifying. So much of my perceived value is housed in this idea that my significance will stay intact if I can keep going. If my productivity wavers or declines, what will that make of me? God forbid someone thinks I’m lazy.

I have worked on this attachment to overproductive behavior before reading On Our Best Behavior, and I have started to do less in the last few years. It was tough at first, but the changes I experienced were remarkable. I got my time back. I began to ask myself what I wanted and needed—something I had never done. Before, there wasn’t enough time to ponder such a question, so I thought.

And besides, what could I possibly need? Fortunately, I have two healthy children, a supportive husband, and a sizable Albanian family that constantly cheers me on. It felt like the only thing I could do was to keep going, keep working, maintain a perfect house, foster multiple friendships and relationships, host as many get-togethers as possible (I still love doing this), and cook healthy meals to nourish my family. Oh, and don’t forget to add work out and stay slim to that list because my 40s reminded me that the body doesn’t always oblige as it used to.

The sin of sloth is insidious in the way so many women are programmed to believe the myth: the busier, the better. There is a perception that if we’re not doing enough, producing enough, and doing it impeccably, then what does that make of our worth?

Ironically, while I was reading the chapter on sloth, I overheard an interesting conversation between my daughter and her best friend talking about their summer break. They’re both 17, good students, and they both have summer jobs lined up.

This was their conversation:

Hana: I don’t want to sleep in a lot this summer; we need to keep busy.

Best friend: I know, I agree. I slept in this morning, and I was mad at myself.

Hana: Same.

Best friend: We need to wake up every day and start off at the gym.

Hana: I know, and I want to make a list every day of the things I have to do so I don’t fall behind.

Best friend: Me too…we have to make sure we keep each other accountable.

Summer break was less than 48 hours underway. They had just completed their final exams, and this was their conversation.

I have a son and a daughter. My son is 20 and entering his junior year of college. While he, too, is productive, I’ve never heard him say he feels bad about sleeping in or that he has to make sure he stays on top of everything so he doesn’t waste the day.

What was happening? This programming had already made its way to the girls, and I’ve never overtly said any of these things. Yes, my husband and I value a good work ethic and have applauded both kids for their efforts. But this has been interpreted differently in each of them based on societal and cultural expectations.

My daughter feels terrible about sleeping in, and my son doesn’t. I don’t think it would dawn on him to feel bad, nor should it. But he has permitted himself to meet his needs. If he’s tired, he sleeps in. If my daughter is tired, she feels guilty for sleeping in and tending to her needs. She perceives it as wasting time.

Elise’s book highlights why we need to have conversations about the underpinnings of these beliefs. The beliefs that tell us if we pause or rest, we’re not doing enough. I’ve never overtly taught productive behavior to either child. They have observed and watched.

The amount of pressure women, mothers especially, put on themselves is not sustainable, and it leaves us drowning, overwhelmed, and suppressed. We’re tethered to an ambitious schedule with little room to create, grow, explore, and learn.

I’ve learned to make peace with the doer in me. I can see when she gets activated, and I have enough awareness to say that’s not what I need to do. I’ve learned to set boundaries that make some unhappy but preserve the sacred time and space I’ve created for myself. Adhering to a practice where I ask myself what I need has dramatically changed how I arrange my days, weeks, and months.

With balance and finding the middle, I’ve come to appreciate busy days, not because I attach my self-worth to them but because I consciously choose the things that keep me busy.

As we say in Albanian, puna eshte shendet. This translates to work, or being able to work or do, is a blessing because it means you’re healthy and well enough to do so. There is gratitude in being productive, but it should be on your terms. We shouldn’t subscribe to the busy-is-best mindset to preserve our self-worth. This creates expectations that are not sustainable, and it leaves us feeling that no matter how much we do, we still seem to fall short.

Pausing before responding to a request has created space for me to hear my voice and determine if something feels like a yes or no. I no longer impulsively say “yes” to ensure I don’t disappoint someone.

Elise writes, “Accepting sloth as essential, we can demand support, embrace rest, and reserve our strength for the worthiest work.”

It didn’t take long for me to love my slower pace. I was recently checking out at Trader Joe’s, and the cashier asked, “What do you have going on this weekend?” I happily said, “Not a thing.” She paused and then said, “Good for you.” Hopefully, we can start to do more of this, cheer each other on and encourage balance, rest and taking a pause.